Turkey, which was made aware of the sensitivity surrounding the Armenian issue throughout the world through attacks by the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASALA), continues to be caught unprepared every year as to how to shape its approach towards the events of April 24.

Turkey, which was made aware of the sensitivity surrounding the Armenian issue throughout the world through attacks by the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASALA), continues to be caught unprepared every year as to how to shape its approach towards the events of April 24.

Turkey, which is on the verge of losing this particular battle, at least in the academic sense, has carried on with this struggle mostly through closing its borders and engaging in verbal clashes with the Armenian diaspora. And now it is quite clear that neither of these tactics have gained much for Turkey. As for Turkey’s efforts with its neighboring countries and with the Armenian diaspora, these have only resulted in the entrance of new genocide bills onto the agenda as well as more pressure from various countries interested in Turkey. In particular, the annual increase in curiosity and expectations concerning what approach the US will embrace on the issue is literally exhausting the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Another factor pushing Turkey into a dead end in the international arena is its lack of public diplomacy efforts aimed at Armenia, as well as the fact that it has not created alternative Turkish lobbying groups in countries where the Armenian lobby is already strong. The fact that April 24 fell on the same day as Easter this year gave Armenians a great opportunity to show their religious and national feelings even more strongly than usual. And in Turkey, the influential rallies that have taken place with regard to this matter show that it is now time to take up the issue with some prudence and level-headedness.

Can the healthy communication skills lacking between Turkey and Armenia instead be formed between Turkey and the latter’s diaspora population?

Mutual efforts

In countries where the Armenian lobby and diaspora are influential, there are frequent Turkish efforts to hold joint festivals, programs and other sorts of meetings with these Armenian groups. Even though it is not constant, Turkey quite regularly tries to create an atmosphere of dialogue with certain Armenian groups. And though political efforts can only go so far, it is the wide network of civil society organizations that can pick up the slack here, succeeding where states are unable. In the very near future, civil society organizations look set to show their influence in helping to find solutions to shared problems. We, too, with our initiatives in the civil society branch of things, are closely examining the Armenian community in the US and working to help create a joint dialogue.

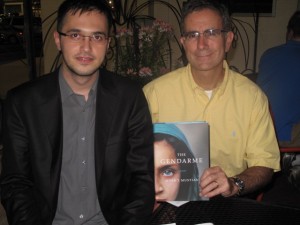

The shared thoughts of most Armenians, regardless of when they arrived in the US, has to do with Turkish acceptance of its historic mistakes, and opening up the way forward for regional cooperation. Lawyer and writer Mark Mustian, whose forefathers came around 200 years ago from Ottoman soil to the US, also thinks this way. The fact that his ancestors, who came to the US to take advantage of the wealth of opportunity there, preserved, at least to some extent, their Armenian identities is what imbues Mustian today with a sense of responsibility towards his fellow Armenians. Mustian, who practiced law for many years in Florida, started writing a novel some years ago about the breaking asunder of the Turkish and Armenian communities. The novel, titled “The Gendarme,” was finished in seven years and then published in the US, France, Spain, Greece, Israel, Italy, Brazil and the UK. Mustian, who says the reason he wrote this book was his own personal sense of discomfort with how the Armenian community in the US lives in ignorance regarding its own history and identity, notes 70 percent of the Armenian diaspora constantly brings historical matters onto the agenda, while another 10 percent live completely ignorant of what the Armenian identity really is. He notes also that the other 20 percent or so maintain moderate approaches to historical matters and identity questions. Mustian, who says he has visited Turkey but has never had the chance to go to Armenia, asserts that he loves Turkey very much and when it comes to the question of relations with Armenia — both Ankara and Yerevan must act on their own accord. He also believes open borders between Turkey and Armenia will improve cultural interactions and that many problems would be solved faster than currently believed.

The shared thoughts of most Armenians, regardless of when they arrived in the US, has to do with Turkish acceptance of its historic mistakes, and opening up the way forward for regional cooperation. Lawyer and writer Mark Mustian, whose forefathers came around 200 years ago from Ottoman soil to the US, also thinks this way. The fact that his ancestors, who came to the US to take advantage of the wealth of opportunity there, preserved, at least to some extent, their Armenian identities is what imbues Mustian today with a sense of responsibility towards his fellow Armenians. Mustian, who practiced law for many years in Florida, started writing a novel some years ago about the breaking asunder of the Turkish and Armenian communities. The novel, titled “The Gendarme,” was finished in seven years and then published in the US, France, Spain, Greece, Israel, Italy, Brazil and the UK. Mustian, who says the reason he wrote this book was his own personal sense of discomfort with how the Armenian community in the US lives in ignorance regarding its own history and identity, notes 70 percent of the Armenian diaspora constantly brings historical matters onto the agenda, while another 10 percent live completely ignorant of what the Armenian identity really is. He notes also that the other 20 percent or so maintain moderate approaches to historical matters and identity questions. Mustian, who says he has visited Turkey but has never had the chance to go to Armenia, asserts that he loves Turkey very much and when it comes to the question of relations with Armenia — both Ankara and Yerevan must act on their own accord. He also believes open borders between Turkey and Armenia will improve cultural interactions and that many problems would be solved faster than currently believed.

Vasken Hagopian and Zohrap Hovsapian are two Armenians who live in Florida and embrace moderate approaches to the topic of relations with Turkey. Hagopian, whose ancestors are from Adana, still works as a professor at the Florida State University in the department of physics and astronomy. During World War I, Hagopian’s family lost many of its members, and the family migrated from Turkey to Syria, Lebanon, France and Greece. His father had worked in churches on Ottoman soil and wrote many of his memories of this period in a book. Hagopian characterizes the relations between Armenia and its diaspora as being “ongoing based on assistance,” and also notes he finds it unlikely Turkey will be admitted to the European Union. Hagopian also says he finds it unthinkable that these two ancient civilizations and peoples could be living right next to one another but be unable to develop a dialogue. He also asserts that it is simply not possible that Armenia could politically make any demands for land from eastern Anatolia.

Vasken Hagopian and Zohrap Hovsapian are two Armenians who live in Florida and embrace moderate approaches to the topic of relations with Turkey. Hagopian, whose ancestors are from Adana, still works as a professor at the Florida State University in the department of physics and astronomy. During World War I, Hagopian’s family lost many of its members, and the family migrated from Turkey to Syria, Lebanon, France and Greece. His father had worked in churches on Ottoman soil and wrote many of his memories of this period in a book. Hagopian characterizes the relations between Armenia and its diaspora as being “ongoing based on assistance,” and also notes he finds it unlikely Turkey will be admitted to the European Union. Hagopian also says he finds it unthinkable that these two ancient civilizations and peoples could be living right next to one another but be unable to develop a dialogue. He also asserts that it is simply not possible that Armenia could politically make any demands for land from eastern Anatolia.

Not without dialogue

As for Hovsapian, his family comes from Silvan in the province of Diyarbakır. The five people from his family that survived the war era emigrated from Syria to France. The elders in his family not only published their own memories of this period, but also changed their surname from Keshishian, which they had used on Ottoman soil, to Hovsapian. As Hovsapian sees it, today’s world is impossible to live in for anyone unwilling to enter into dialogue. Hovsapian, who also asserts that the Soviet Union eliminated national consciousness, says that for him Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points are very important. These principles stress that for nations of people to offer up their fates to states or to have their fates taken from their hands by these same states is very unfair. Hovsapian, who we learn has many friends in Turkey, believes that it is of vital importance that Turkey develop its relations with Armenia in the near future, and that both countries get involved in shared projects. He is quite sure that Turkey and Armenia, working together, can achieve great success. In the end, both of these men state that peace without dialogue is impossible and that everyone must do their part in bringing about progress on this front.

As for Hovsapian, his family comes from Silvan in the province of Diyarbakır. The five people from his family that survived the war era emigrated from Syria to France. The elders in his family not only published their own memories of this period, but also changed their surname from Keshishian, which they had used on Ottoman soil, to Hovsapian. As Hovsapian sees it, today’s world is impossible to live in for anyone unwilling to enter into dialogue. Hovsapian, who also asserts that the Soviet Union eliminated national consciousness, says that for him Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points are very important. These principles stress that for nations of people to offer up their fates to states or to have their fates taken from their hands by these same states is very unfair. Hovsapian, who we learn has many friends in Turkey, believes that it is of vital importance that Turkey develop its relations with Armenia in the near future, and that both countries get involved in shared projects. He is quite sure that Turkey and Armenia, working together, can achieve great success. In the end, both of these men state that peace without dialogue is impossible and that everyone must do their part in bringing about progress on this front.

Over time, these two communities of Turks and the Armenians, who have been so closely linked — as neighbors, countrymen, classroom friends, in-laws and work colleagues — have experienced a distancing from one another as a result of a 100-year break, but this break has not managed to erase the traces of 1,000 years of togetherness. The preconceptions brought about by political approaches on both sides have invested both sides with much hesitation as to which steps to take. On one hand, you have nations of people unable to form dialogues, while on the other hand you have diaspora groups that cannot seem to meet in the middle; these factors are causing the whole matter to continue as a sort of an incurable syndrome. To rid itself of this syndrome, Turkey needs to increase its public diplomacy towards Armenia, as well as take steps that will work for Armenians in both the East and the West. Because what Armenia really needs these days are words on the topic of possible cooperative efforts, not on conflict or disagreement. In any case, it is quite clear to whom all this enmity is really causing damage and to whom it is advantageous.

Mehmet Fatih ÖZTARSU

Mayıs 2nd, 2011

Mayıs 2nd, 2011  oztarsu

oztarsu  Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags: